Ho‘okuleana – it’s an action word; it means, “to take responsibility.” We view it as our individual and collective responsibility to: Participate … rather than ignore; Prevent … rather than react and Preserve … rather than degrade. This is not really a program, it is an attitude we want people to share. The world is changing; let’s work together to change it for the better. (All Posts Copyright Peter T Young, © 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 Hoʻokuleana LLC)

Showing posts with label Manoa. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Manoa. Show all posts

Saturday, March 14, 2015

Kahalaopuna

During the days of Kākuhihewa, ruling chief of O‘ahu from about 1640 to 1660, Kahaukani ((K) Mānoa wind) and Kaʻaukuahine ((W) Mānoa rain) were brother and sister twins. When the children were grown up, their foster parents decided they should be united; they were married and Kahalaopuna was born to them – a uniting of the Mānoa wind and rain. She is deemed of semi-supernatural descent.

Kahalaopuna “was so beautiful that a rainbow followed her wherever she went.” “A rosy light seemed to envelop the house, and bright rays seemed to play over it constantly. When she went to bathe in the spring below her house, the rays of light surrounded her like a halo.” She was killed by Kauhi. Today, you can still find the spirit of Kahalaopuna (the Princess of Mānoa) in the ānuenue (rainbows) spanning Mānoa Valley.

Click HERE for the full post and more images.

Thursday, June 5, 2014

Pukaʻōmaʻomaʻo

Traditions on the island of Oʻahu note Mā’ilikūkahi was a ruling chief around 1500 (about the time Columbus crossed the Atlantic.) Māʻilikūkahi is said to have enacted a code of laws in which theft from the people by chiefs was forbidden.

A son of Mā’ilikūkahi was Kalona-nui, who in turn had a son called Kalamakua. Kalamakua is said to have been responsible for developing a large system of taro planting across the Waikīkī-Kapahulu-Mōʻiliʻili-Mānoa area. The extensive loʻi kalo were irrigated by water drawn from the Mānoa and Pālolo Valley streams and large springs in the area.

In 1792, Captain George Vancouver described Mānoa Valley on a hike from Waikīkī in search of drinking water: “We found the land in a high state of cultivation, mostly under immediate crops of taro; and abounding with a variety of wild fowl chiefly of the duck kind …”

“The sides of the hills, which were in some distance, seemed rocky and barren; the intermediate vallies, which were all inhabited, produced some large trees and made a pleasing appearance. The plains, however, if we may judge from the labour bestowed on their cultivation, seem to afford the principal proportion of the different vegetable productions …” (Edinburgh Gazetteer)

One century later, before it was urbanized, Mānoa Valley was described by Thrum (1892:) “Manoa is both broad and low, with towering hills on both sides that join the forest clad mountain range at the head, whose summits are often hid in cloud land, gathering moisture there from to feed the springs in the various recesses that in turn supply the streams winding through the valley, or watering the vast fields of growing taro, to which industry the valley is devoted. The higher portions and foot hills also give pasturage to the stock of more than one dairy enterprise.”

Handy (in his book Hawaiian Planter) writes that in ancient days, all of the level land in upper Mānoa was developed into taro flats and was well-watered, level land that was better adapted to terracing than neighboring Nuʻuanu. The entire floor of Mānoa Valley was a “checkerboard of taro patches.” “The terraces extended along Manoa Stream as far as there is a suitable land for irrigating.”

The well-watered, fertile and relatively level lands of Mānoa Valley supported extensive wet taro cultivation well into the twentieth century. Handy and Handy estimated that in 1931 “there were still about 100 terraces in which wet taro was planted, although these represented less than a tenth of the area that was once planted by Hawaiians.” (Cultural Surveys)

Mānoa Valley was a favored spot of the Ali‘i, including Kamehameha I, Chief Boki (Governor of O‘ahu), Haʻalilio (an advisor to King Kamehameha III,) Princess Victoria, Kanaʻina (father of King Lunalilo), Lunalilo, Keʻelikōlani (half-sister of Kamehameha IV) and Queen Lili‘uokalani. The chiefs lived on the west side, the commoners on the east.

Queen Kaʻahumanu lived there; her home was called Pukaʻōmaʻomaʻo (Green Gateway.) It was situated deep in the valley (lit., green opening; referring to its green painted doors and blinds - It is alternatively referred to as Pukaʻōmaʻo.)

“Her residence is beautifully situated and the selection of the spot quite in taste. The house … stands on the height of a gently swelling knoll, commanding, in front, an open and extensive view of all the rich plantations of the valley; of the mountain streams meandering through them … of the district of Waititi; and of Diamond Hill, and a considerable part of the plain, with the ocean far beyond.” (Stewart; Sterling & Summers)

It was doubtless the same sort of grass house which was in general use, although probably more spacious and elaborate as befitted a queen. The dimension in one direction was 60 feet. The place name of the area was known as Kahoiwai, or "Returning Waters."

“Immediately behind the house, and partially flanking it on either side, is a delightful grove of the dark leaved and crimson blossomed ʻŌhia, so thick and so shady … filled with cool and retired walks and natural retreats, and echoing to the cheerful notes of the little songsters, who find security in its shades to build their nests and lay their young.”

“The view of the head of the valley inland, from the clumps and single trees edging this copse, is very rich and beautiful; presenting a circuit of two or three miles delightfully variegated by hill and dale, wood and lawn, and enclosed in a sweep of splendid mountains, one of which in the centre rises to a height of three thousand feet.”

“In one edge of this grove, a few rods from the house, stands a little cottage built by Kaahumanu, for the accommodation of the missionaries who visit her when at this residence. … (It) is very frequently occupied a day or two at a time, by one and another of the families most enervated by the heat and dust, the toil, and various exhausting cares of the establishment at the sea-shore.“ (Stewart; Sterling & Summers)

“Not far makai … High Chief Kalanimōku, had very early allotted to the Mission the use of farm plots thus noted in its journal of June, 1823: "On Monday the 2d, Krimakoo and the king's mother granted to the brethren three small pieces of land cultivated with taro, potatoes, bananas, melons, &c. and containing nineteen bread-fruit trees, from which they may derive no small portion of the fruit and vegetables needed by the family.” (Damon)

Then, in mid-1832, Kaʻahumanu became ill and was taken to her house in Mānoa, where a bed of maile and leaves of ginger was prepared. “Her strength failed daily. She was gentle as a lamb, and treated her attendants with great tenderness. She would say to her waiting women, 'Do sit down; you are very tired; I make you weary.’” (Bingham)

“The king, his sister, other members of the aliʻi and many retainers had already arrived at Pukaomaomao and had dressed the large grass house for the dying queen's last homecoming. The walls of the main room had been hung with ropes of sweet maile and decorated with lehua blossoms and great stalks of fragrant mountain ginger.”

“The couch upon which Kaahumanu was to rest had been prepared with loving care. Spread first with sweet-scented made and ginger leaves, it was then covered with a golden velvet coverlet. At the head and foot stood towering leather kahilis. Over a chair nearby was draped the Kamehameha feather cloak which had been worn by Kaahumanu since the monarch's death.” (Mellon; Sterling & Summers)

“The slow and solemn tolling of the bell struck on the pained ear as it had never done before in the Sandwich Islands. In other bereavements, after the Gospel took effect, we had not only had the care and promise of our heavenly Father, but a queen-mother remaining, whose force, integrity, and kindness, could be relied on still.”

“But words can but feebly express the emotions that struggled in the bosoms of some who counted themselves mourners in those solemn hours; while memory glanced back through her most singular history, and faith followed her course onward, far into the future.” (Hiram Bingham)

Her death took place at ten minutes past 3 o’clock on the morning of June 5, 1832, “after an illness of about 3 weeks in which she exhibited her unabated attachment to the Christian teachers and reliance on Christ, her Saviour.” (Hiram Bingham)

The image shows Kaʻahumanu (drawn by Herb Kane.) In addition, I have added other images in a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

Follow Peter T Young on LinkedIn

© 2014 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Wednesday, March 26, 2014

Mānoa Valley Inn

The first subdivision in Mānoa was the Seaview tract, in Lower Mānoa near Seaview Street, which was laid out in 1886 (this area in the valley became known as the "Chinese Beverly Hills" due to the high percentage of people of that ethnic group buying into the neighborhood (1950s.)) (DeLeon)

In 1888, the animal-powered tramcar service of Hawaiian Tramways ran track from downtown to Waikīkī. In 1900, the Tramway was taken over by the Honolulu Rapid Transit & Land Co (HRT.)

In addition to service to the core Honolulu communities, HRT expanded to serve other opportunities. In the fall of 1901, a line was sent up into central Mānoa. The new Mānoa trolley opened the valley to development and rushed it into the expansive new century.

Originally numerous large, well-designed houses lined Vancouver Drive; however with the passing of the years many of these dwellings have disappeared. One of approximately a half dozen remnants of the earlier time which are scattered in the area is the subject of this summary.

The lot and house had been previously owned by Benjamin Dillingham, founder of the Oahu Railway and Land Company; Richard Bickerton, Supreme Court Justice and Privy Council Member under Queen Liliʻuokalani; Grace Merrill, sister of Architect Charles Dickey, and wife of Arthur Merrill, principal of Mid Pacific Institute. (NPS)

The John Guild House, now known as Mānoa Valley Inn at 2001 Vancouver Drive, was purchased in 1919 by John Guild, a Honolulu businessman. It had been built four years earlier by Iowa lumber dealer Milton Moore and has been refurbished and restored several times over its lifespan. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002.

Predating Hawaiʻi zoning laws by some fifty years, the Seaview area was one of the first areas to impose restrictive covenants for design and view planes. It is likely that this is the reason that John Guild remodeled an earlier house on this site, rather than rebuilding a new house.

Prior to the 1919 major remodeling, the Guild residence was a large two-story bungalow style house which featured brown shingles. Guild added the large brackets, outset square projections, porte cochere and inset centered porch.

The house was purchased in the 1980s by Honolulu businessman Rick Ralston (the founder of Crazy Shirts), who restored it in 1982 for use as a bed and breakfast under the name John Guild Inn, later Mānoa Valley Inn. Several other transactions followed.

It’s now a 4,424-square-foot, three-story gabled cottage near the campus of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, operating as a bed and breakfast with six bedrooms, a suite and a small cottage and a broad, sheltered lanai with a view over the city on the sea side of the house. The rooms are furnished with fine antiques.

Let’s go back to the home’s original namesake, John Guild.

Guild was born May 11, 1869, in Edinburgh, Scotland; he was son of James (a merchant of Edinburgh) and Mary (Scott) Guild. After leaving school he went to join relatives interested in the sugarcane industry in the West Indies. He married Mary Knox there on August 20, 1891; they had four children, Dorothy, Marjorie, Douglas Scott and Winifred.

He came to Hawaii 1897 and for short time was employed on Makaweli plantation; he later joined Alexander & Baldwin, then a co-partnership (incorporated 1900) and worked his way to being a Director and Secretary of A&B and in all the companies they represented. He had quite a share in the development of the concern.

Guild’s prominent presence came to an abrupt end.

A New York Times headline tells the story: “ADMITS $750,000 Shortage; John Guild Manipulated Surplus Cash of Honolulu Firm”

“John Guild, formerly secretary and director of Alexander & Baldwin and honored member of the business and social communities of Honolulu is now No. E-512 in the Oahu penitentiary. He is employed in garden work…” (Maui News, August 29, 1922)

“(T)he grand jury found two true bills of indictment against him, one for embezzling bonds from the Episcopal Church and the other for embezzling $37,000 from Alexander & Baldwin in 1917.”

“On Saturday morning Guild was taken before Judge Banks and pleaded guilty to both indictments. He was sentenced to serve in the Oahu penitentiary at hard labor two terms of not less than five nor more than ten years, to run consecutively.”

“This would mean that with allowance for good behavior he may be released in between seven and eight years, if he lives to finish his sentence.” (Maui News, August 29, 1922)

Only two indictments were issued, “though more than a hundred might have been more were claimed.” It was reported that the A&B books showed that Guild’s embezzlement was in excess of a million dollars.

The house was sold to the company for $1 and Guild was sent to prison where he died in 1927. In 1925, merchant Arthur J Spitzer and his wife Selma purchased the house. They lived here until 1970.

The house later fell on hard times and was used as a student rooming house. The building was scheduled for demolition in 1978, when it was bought and renovated by Ralston and continues to be a very active bed and breakfast.

The image shows the former John Guild house, now the Mānoa Valley Inn. I have added other images to a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

© 2014 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Sunday, March 2, 2014

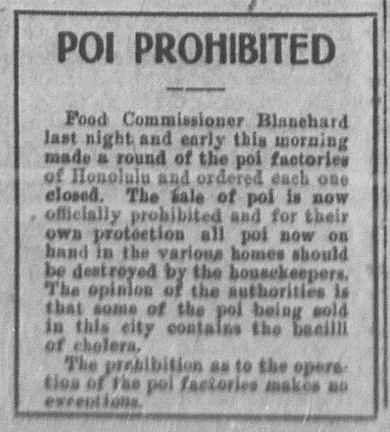

Poi Prohibited

"The sale of poi is now officially prohibited."

Thus was the March 2, 1911 directive of Food Commissioner Blanchard (as noted in an announcement on the front page of the Hawaiian Gazette, March 3, 1911.) (While not being sold, there was still plenty of poi available to consumption.)

"Over seventy-five hundred pounds of poi is being distributed free every day to Hawaiians in this city by the board of health under a resolution by the legislature appropriating $2000 out of the contingent fund for the expense subject to the approval of the Governor." (Hawaiian Gazette, March 10, 1911)

"About one ton of poi a day is given out at each of the four stations Kalihi, Palama, Mōʻiliʻili and Kawaiahaʻo Church. At each place there is a health inspector representing the board of health who is in charge of the operation assisted by deputies of Mr Rath superintendent of the Palama settlement work, who is superintending the poi distribution." (Hawaiian Gazette, March 10, 1911)

"At first the distribution was in the shape of sacks of poi of about ten pounds each put up at the Kalihi factory but such a great demand was immediately developed that the factory had no time to sack the poi and now it is being sent to the distributing points in barrels." (Hawaiian Gazette, March 10, 1911)

"A number of bacteriological tests made with poi have convinced the health officers of the territorial and federal government that that staple can transmit and impart the germs of cholera and probably all other disease of similar nature." (Hawaiian Gazette, March 17, 1911)

"With but two exceptions every case of cholera in the two outbreaks during the past two months has been traced to one source of infection - the Manoa valley taro patches and the poi manufactured from this taro." (Hawaiian Gazette, April 18, 1911)

"In Manoa valley is a Chinese named Hong Fong who had a taro patch. He carried taro to a shop on Fort street near School. This was made into poi and each day he carried poi from this shop up to Manoa and delivered it to Manana and Mrs Gonsalves who were the first of the Manoa cases." (Hawaiian Gazette, April 18, 1911)

"Then comes the Perry family cases in Manoa where cholera wiped out almost an entire family. There were four cases of cholera. They lived on the bank near this taro field. They raised their own taro but sometimes bought poi from Hong Fong. They filled their water barrels for drinking purposes from this stream which had been contaminated by Manana when he became sick." (Hawaiian Gazette, April 18, 1911)

"In this stream Manana's contaminated clothing was washed by members of his family and water from this polluted stream was used to mix with poi. A Japanese dairyman nearby used this water to dilute the milk product and the children in the Perry family drank milk so diluted and contaminated." (Hawaiian Gazette, April 18, 1911)

"From February 25, when the first case was reported, to March 14, 1911, the date of the last case, there had been reported a total of 31-cases with 22 deaths. Twenty four days having elapsed since the occurrence of the last case, Honolulu may properly be considered to no longer harbor the disease." (Public Health Reports)

The medical conditions led the territorial legislature to enact regulations on the processing of poi. The "Poi Bill" gave the board of health the authority to close any poi shop which is found to be making poi under filthy and disease-breeding conditions (the first law to regulate poi factories.)

This is not the Islands' last legislative fight over processing poi.

A hundred years later, in 2011, another "Poi Bill" (SB101) was enacted after it made its way through the legislature and onto the Governor's desk.

It exempted paʻi ʻai (traditional "hand-pounded poi") from certain food-processing requirements/permits under certain conditions. (Up to that passage, the Department of Health deemed paʻi ʻai unsafe.)

(Cholera is an infection of the small intestine caused by the bacteria; the main symptoms are watery diarrhea and vomiting. It is typically transmitted by either contaminated food or water. Worldwide, there have been several cholera pandemics, killing millions of people.)

The image shows Food Commissioner's Poi Prohibition proclamation. (Hawaiian Gazette, March 3, 1911) In addition, I have added other images in a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

© 2014 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Tuesday, November 12, 2013

Ala Wai Canal

A son of Mā’ilikūkahi (who ruled about the time Columbus crossed the Atlantic) was Kalona-nui, who in turn had a son called Kalamakua. Kalamakua is said to have been responsible for developing large taro gardens in what was once a vast area of wet-taro cultivation on Oʻahu: the Waikiki-Kapahulu-Mōʻiliʻili-Mānoa area.

The early Hawaiian settlers gradually transformed the marsh above Waikīkī Beach into hundreds of taro fields, fish ponds and gardens. For centuries, springs, taro lo‘i, rice paddies, fruit and vegetable patches, duck ponds and fishing areas were a valuable means of subsistence for native Hawaiians and others.

Formerly the home of Hawaiian royalty, including King Kamehameha, Waikīkī, meaning “spouting waters,” once covered a much broader area than it does today.

The ahupuaʻa, or ancient land division, of Waikīkī actually covered the area extending from Kou (the old name for Honolulu) to Maunalua (now referred to as Hawai’i Kai).

Waikīkī’s marshland, the boundaries of which changed seasonally, once covered about 2,000-acres (about four times the size of Waikīkī today) before the marshes were drained.

During the first decade of the 20th-century, the US War Department acquired more than 70-acres in the Kālia portion of Waikīkī for the establishment of a military reservation called Fort DeRussy.

They drained and filled the area, so they could build on it. Thus, the Army began the transformation of Waikīkī from wetlands to solid ground.

In the early-1900s, Lucius Pinkham, then President of the Territorial Board of Health and later Governor, developed the idea of constructing a drainage canal to drain the wetlands, which he considered "unsanitary." This called for the construction of a canal to reclaim the marshland.

The Waikīkī Reclamation District was identified as the approximate 800-acres from King and McCully Streets to Kapahulu Street, near Campbell Avenue down to Kapiʻolani Park and Kalākaua Avenue on the makai side (1921-1928.) The dredge material not only filled in the makai Waikīkī wetlands, it was also used to fill in the McKinley High School site.

During the 1920s, the Waikīkī landscape would be transformed when the construction of the Ala Wai Drainage Canal, begun in 1921 and completed in 1928, resulted in the draining and filling in of the remaining ponds and irrigated fields of Waikīkī.

The initial planning called for the extension of the Ala Wai Canal past its present terminus and excavate along Makee Island in Kapiʻolani Park, connecting the Canal with the ocean on the Lēʻahi side of the project. However, funds ran short and this extension was contemplated “at some later date, when funds are made available”; however, that never occurred.

By 1924, the dredging of the Ala Wai Canal and filling of the wetlands stopped the flows of the Pi‘inaio, ‘Āpuakēhau and Kuekaunahi streams running from the Makiki, Mānoa, and Pālolo valleys to and through Waikīkī.

Walter F. Dillingham's Hawaiian Dredging Company dredged the canal and sold the material he had dredged to create the canal to build up the newly created land. The canal is still routinely dredged, most recently in 2003.

During the course of the Ala Wai Canal’s initial construction, the banana patches and ponds between the canal and the mauka side of Kalākaua Avenue were filled and the present grid of streets was laid out. These newly created land tracts spurred a rush to development.

With construction of the Ala Wai Canal, 625-acres of wetland were drained and filled and runoff was diverted away from Waikīkī beach. The completion of the Ala Wai Canal not only gave impetus to the development of Waikīkī as Hawai‘i’s primary visitor destination, but also expanded the district’s potential for residential use.

During the period 1913-1927, the demand for housing in Honolulu grew along with the city’s population. Waikīkī helped satisfy this demand; the large kamaʻāina landholdings virtually disappeared and the area started to be subdivided.

Before reclamation, assessed values for property were at about $500-per acre and the same property was reclaimed at ten cents per square foot, making a total cost of $4,350-per acre. The selling price after reclamation, $6,500 to $7,000-per acre, showed the financial benefit of the reclamation efforts.

From an economic point of view, without the Ala Wai Canal, Waikīkī may never have developed into the worldwide tourist attraction it is today.

In 1925, the City Planning Commission requested the citizens of Honolulu to submit suitable Hawaiian names for the renaming of the Waikīkī Drainage canal; twelve names were suggested.

The Commission felt that Ala Wai (waterway,) the name suggested by Jennie Wilson was the "most euphonic". (An engineer with the Planning Commission was quick to note that, "the fact that Mrs. Wilson is the mayor's wife had nothing to do with the choice of the name.")

In November 1965, a storm, classified as a 25-year event, overflowed the Ala Wai Canal banks and flooded Ala Wai Boulevard.

Ala Wai Canal and the historic walls lining the canal are owned by the State of Hawaiʻi. The promenades on the mauka side of the Ala Wai Canal are owned by the State, and by, Executive Ordered to the City and County of Honolulu, the promenades on the makai side are owned by the City. The promenades on both sides of the Ala Wai Canal are maintained by the City Department of Parks and Recreation

The Ala Wai Canal is listed in the National and State registers of historic places.

The image shows the Ala Wai Canal in about 1925. In addition, I have included more images on the Ala Wai Canal in a folder of like name in the Photos section.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

© 2013 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Saturday, June 1, 2013

“Miss Ball Won The Fight For Others”

A healer touches people.

A good healer touches a person’s body, mind and spirit.

A great healer touches many people’s lives.

In attempting to describe a healer who touches the lives of thousands of sufferers around the world may lead us to call that individual a saint.

Saint Damien is appropriately recognized for his commitment in easing the suffering and caring for the thousands of suffering souls, banished to Kalaupapa because they had Hansen’s disease.

An almost forgotten healer was a young (24-years old) Black chemist and pharmacist, who made a revolutionary discovery that changed the lives of Hansen's disease sufferers.

Once known as leprosy, the disease was renamed after Dr. Gerharad Armauer Hansen, a Norwegian physician, when he discovered the causative microorganism in 1873, the same year that Father Damien volunteered to serve at Kalaupapa.

Born on July 24, 1892 in Seattle, Washington, Alice Augusta Ball was the daughter of James P Ball and his wife, Laura; she lived in a middle or even upper-middle class household.

Ball’s grandfather, JP Ball, Sr, a photographer, was one of the first Blacks in the US to learn the art of daguerreotype and created in Cincinnati one of the more famous daguerreotype galleries. During his lifetime, Ball also opened photography galleries in Minneapolis, Helena, Montana, Seattle and Honolulu, where he died at the age of 79.

After moving to Hawaiʻi in 1903 and attending elementary school here, Alice Ball and her family moved back to the continent where she attended high school in Seattle, earning excellent grades, especially in the sciences.

After a stint with the family living in Montana and then returning to Seattle, Alice Ball entered the University of Washington and graduated with two degrees in pharmaceutical chemistry in 1912 and pharmacy in 1914.

In the fall of 1914, she entered the College of Hawaiʻi (later called the University of Hawaiʻi) as a graduate student in chemistry.

On June 1, 1915, she was the first African American and the first woman to graduate with a Master of Science degree in chemistry from the University of Hawaiʻi. In the 1915-1916 academic year, she also became the first woman to teach chemistry at the institution.

But the significant contribution Ball made to medicine was a successful injectable treatment for those suffering from Hansen’s disease.

She isolated the ethyl ester of chaulmoogra oil (from the tree native to India) which, when injected, proved extremely effective in relieving some of the symptoms of Hansen’s disease.

Although not a full cure, Ball’s discovery was a significant victory in the fight against a disease that has plagued nations for thousands of years. The discovery was coined, at least for the time being, the “Ball Method.”

A College of Hawaiʻi chemistry laboratory began producing large quantities of the new injectable chaulmoogra. During the four years between 1919 and 1923, no patients were sent to Kalaupapa – and, for the first time, some Kalaupapa patients were released.

Ball's injectable compound seemed to provide effective treatment for the disease, and as a result the lab began to receive "requests for their chaulmoogra oil preparations from all over the world.”

“The annals of medical science are incomplete unless full credit is given for the work of Alice Ball. … It was no easy task. One after another the various preparations were tried and put aside. … It led to the discovery of the preparation which bids fair to become a specific in the treatment of leprosy. Miss Ball won the fight for others”. (American Missionary Association, April 1922)

The “Ball Method” continued to be the most effective method of treatment until the 1940s and as late as 1999 one medical journal indicated the “Ball Method” was still being used to treat Hansen disease patients in remote areas.

At the time of her research Ball became ill. She worked under extreme pressure to produce injectable chaulmoogra oil and, according to some observers, became exhausted in the process.

Unfortunately, Ball never lived to witness the results of her discovery. She returned to Seattle and died at the age of 24 on December 31, 1916. The cause of her death was unknown.

On February 29, 2000, the Governor of Hawaiʻi issued a proclamation, declaring it “Alice Ball Day.” On the same day the University of Hawaiʻi recognized its first woman graduate and pioneering chemist with a bronze plaque mounted at the base of the lone chaulmoogra tree on campus near Bachman Hall.

In January 2007, Alice Augusta Ball was presented posthumously the University of Hawaiʻi Regents’ Medal of Distinction, an award to individuals of exceptional accomplishment and distinction who have made significant contributions to the University, state, region or nation or within their field of endeavor.

The image shows Alice Augusta Ball (1915 UH graduation) and the memorial chaulmoogra tree (outside Bachman Hall.) (Lots of information from UH They Followed The Trade Winds.) In addition, I have included other images in a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

© 2013 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Tuesday, May 14, 2013

Gladstone

A memorial chiseled into a hard to find boulder is a vigilant reminder of the hazards of hiking in Hawaiʻi’s wilderness – and it continues the memory of its focus.

We often read about rockfalls on houses, cars and other property; in this case a 7½-pound rock killed a boy on a hike in Mānoa Valley.

The sentinel, with a cross carved into a neighboring boulder, commemorates the tragic death of a young boy on a Sunday school outing.

The Sunday school teacher carried him unconscious down the trail to his carriage and drove to Queen's Hospital; there, treated by Dr. Hildebrand, unfortunately, he died. (Krauss)

He was 11-years old, the son of Thomas and Elizabeth Wright. They came to Hawaiʻi in the early-1880s. Apparently, Thomas was a carriage maker who came to Hawaiʻi with two brothers who apparently operated a carriage business. (Krauss)

The memorial simply states: Gladstone Wright Killed May 14 1891

Apparently, Gladstone’s cousin was George Fred Wright (April 23, 1881 – July 2, 1938,) later Mayor of Honolulu from 1931 to 1938. Wright, a native of Honolulu, died in office in 1938 while traveling aboard the SS Mariposa. (Krauss) (Mayor Wright Housing in Kalihi was named after him.)

The memorial is located on Waiakeakua Stream in Mānoa Valley. It’s between its upper and lower falls on the east side of Mānoa Valley.

Waiakeakua (“Water of the Gods”) is the easternmost spring and stream at the back of Mānoa Valley. Only the high chiefs were allowed to use this spring; it was kapu to others. A chief would often test the courage and fidelity of a retainer by dispatching him at night to fill a gourd at this spring. (Beckwith)

Legends tell of Kāne and Kanaloa in Mānoa Valley.

“As they stood there facing the cliff, Kanaloa asked his older brother if there were kupua (descendants of a family of gods and has the power of transformation into certain inherited forms) in that place. The two climbed a perpendicular cliff and found a pretty woman living there with her woman attendant.”

“Kamehaʻikana (‘a multitude of descendants’) was the name of this kupua. Such was the nature of the two women that they could appear in the form of human beings or of stones. Both Kane and Kanaloa longed to possess this beauty of upper Manoa. The girl herself, after staring at them, was smitten with love for the two gods.”

“Kamehaʻikana began to smile invitingly. The attendant saw that her charge did not know which one of the two gods she wanted and knew that if they both got hold of her, she would be destroyed, and she was furious. Fearing death for her beloved one, she threw herself headlong between the strangers and her charge and blocked the way. Kane leaped to catch the girl, but could not reach her. … The original trees are dead but their seedlings are grown and guard Waiakeakua, Water of the Gods.” (hawaii-edu)

Regarding the trickling stream, Pukuʻi’s ʻŌlelo Noʻeau, No. 2917 notes, Wai peʻepeʻe palai o Waiakekua. The water that plays hide-and-seek among the ferns.

Waihi is a tributary that feeds into Waiakeakua. Just east of the popular Mānoa Falls are three other waterfalls: Luaʻalaea (pit of red earth), just off of the Luaʻalaea trail; the tall Nāniuʻapo (the grasped coconuts), which also has a fresh spring; and Waiakeakua Falls, which features bathing pools. (MalamaOManoa)

The spring, Pūʻahuʻula, just west of Waiakeakua Stream is where Queen Kaʻahumanu, the favorite wife of Kamehameha I, had a green-shuttered home near Pūʻahuʻula, where she died in 1832. (MalamaOManoa)

The image shows the Gladstone memorial. It is off Na Ala Hele’s Puʻu Pia trail, down to and up the Waiakeakua Stream. In addition, I have added other images in a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

© 2013 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Monday, March 25, 2013

University of Hawaiʻi – Mānoa

“An act to establish the College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts of the Territory of Hawai‘i” was passed by the Hawai‘i’s Territorial Legislature and was signed into law by Governor George Carter on March 25th, 1907.

The University of Hawaiʻi began as a land-grant college, initiated out of the 1862 US Federal Morrill Act funding for “land grant” colleges.

The Morrill Act funded educational institutions by granting federally-controlled land to the states for them to develop or sell to raise funds to establish and endow "land-grant" colleges.

Since the federal government could not "grant" land in Hawaiʻi as it did for most states, it provided a guarantee of $30,000 a year for several years, which increased to $50,000 for a time.

Regular classes began in September 1908 with ten students (five freshmen, five preparatory students) and thirteen faculty members at a temporary Young Street facility in the William Maertens' house near Thomas Square.

The Territory had just acquired the Maertens' property as a potential site for a new high school. Instead, it became temporary quarters for the new college.

Planning for a permanent University campus originally called for Lahainaluna on Maui as the site; Mountain View, above Hilo, was also considered.

The regents chose the present campus location in lower Mānoa on June 19, 1907. In 1911, the name of the school was changed to the “College of Hawaiʻi.”

The campus was a relatively dry and scruffy place, “The early Mānoa campus was covered with a tangle of kiawe trees (algarroba), wild lantana and panini cactus”. It appears the first structures built were a poultry shed and a dairy barn.

1909 marked the beginning of the school’s first football team, called the Fighting Deans; the team played its opening game against McKinley High School ... and won.

In 1912, the college moved to the present Mānoa location (the first permanent building is known today as Hawaiʻi Hall.) The first Commencement was June 3, 1912.

The "orienting" of the new campus was determined by the Morrill Act, which saw "land grant" colleges as occupying large squares or rectangles, arranged by surveyors along the cardinal points of the compass. Thus the original quadrangle of so many campuses (including UH) is laid out on a true compass base, ignoring in the process our mauka/makai orientations, ignoring the flow of the trade winds.

With the addition of the College of Arts and Sciences in 1920, the school became known as the University of Hawaiʻi. The Territorial Normal and Training School (now the College of Education) joined the University in 1931.

The University continued to grow throughout the 1930s. The Oriental Institute, predecessor of the East-West Center, was founded in 1935, bolstering the University’s mounting prominence in Asia-Pacific studies.

World War II came to Hawaiʻi with the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Classes were suspended for two months and gas masks became part of commencement apparel. In 1942, students of Japanese ancestry formed the Varsity Victory Volunteers and many later joined the 442nd Regiment and 100th Infantry Battalion.

Statehood brought about a significant shift in the relationship of the University to the land it occupied. Under territorial government, the land was really on loan; the Territory had title.

The new state constitution stated, "The University of Hawaii is hereby established as the state university and constituted a body corporate. It shall have title to all the real and personal property now or hereafter set aside or conveyed to it. ... "

One effect has been that now the State may occasionally choose to lease land to the University, rather than set it aside, because once given, such land becomes University property.

UH Mānoa’s School of Law opened in temporary buildings in 1973. The Center for Hawaiian Studies was established in 1977 followed by the School of Architecture in 1980.

The School of Ocean and Earth Sciences and Technology was founded eight years later and in 2005 the John A Burns School of Medicine moved to its present location in Honolulu's Kakaʻako district.

From its initial enrollment of 10 in 1907, the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa now schools over 20,000.

In the 1950s, after three years of offering UH Extension Division courses at the old Hilo Boarding School, the University of Hawai‘i, Hilo Branch, was approved; the UH Community Colleges system was established in 1964.

Today, the University of Hawai‘i System includes 3 universities (Mānoa, Hilo and West Oʻahu,) 7 community colleges (Kauaʻi, Leeward, Honolulu, Kapiʻolani, Windward, Maui and Hawaiʻi) and community-based learning centers across Hawai‘i.

The fall 2012 opening enrollment for the University of Hawai‘i System reached yet another high in the institution’s history with over 60,600 students.

The image shows an aerial view of the initial UH-Mānoa campus in late-19102 (UH Manoa.) In addition, I have added other related images in a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

© 2013 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Monday, March 18, 2013

College Hill

In 1829, Governor Boki gave the land to Hiram Bingham – who subsequently gave it to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) – to establish Punahou School.

Founded in 1841, Punahou School (originally called Oʻahu College) was built at Kapunahou to provide a quality education for the children of Congregational missionaries, allowing them to stay in Hawaiʻi with their families, instead of being sent away to school. The first class had 15 students.

The land area of the Kapunahou gift was significantly larger than the present school campus size. Near the turn of the last century, the Punahou Board of Trustees decided to subdivide some of the land – they called their subdivision “College Hills.”

Inspired by the garden suburb ideals then becoming popular both in North America and Europe, and especially England, College Hills was initiated as a way of raising revenue for the school.

College Hills was one of several enclaves for Honolulu’s wealthier residents and marked the true beginning of park-like suburban developments in Hawaiʻi.

Following upon earlier subdivisions, such as the 1886 Seaview Tract in the area now known as “lower Manoa,” the College Hills Tract was an important real estate development in the history of Honolulu.

Using nearly 100 acres of land previously leased out as a dairy farm, Punahou subdivided the rolling landscape into separate parcels of from 10,000- to 20,000-square feet.

The “Atherton House” was built on one of the most attractive of these parcels (actually six lots purchased together.) Situated on a slight rise, and protected by the hillside of Tantalus rising to the west (Ewa) side, the Atherton House, part of the new wave of Mānoa residences. It represented the move of one of Hawaiʻi’s elite families into an area thought before to be countryside.

College Hills soon became a desirable residential area served by a streetcar, which traveled up O‘ahu Avenue and made a wide U-turn around the Atherton home on Kamehameha Avenue.

The Atherton House was the residence of Frank C Atherton and his wife Eleanore from 1902 until his death in 1945. (Mrs. Atherton continued living in the house until the early-1960s.)

Designed by architect Walter E Pinkham, the shingled two-story wood-framed house reflects the influence of the late Queen Anne, Prairie and Craftsman styles, but its lava rock piers, ʻōhia floors and large lanai denote it as Hawaiian.

The house was a gift to Atherton from his father, Joseph Ballard Atherton, the family patriarch in Hawaiʻi, who was one of a small group of North Americans and Europeans that became prominent in Hawaiʻi’s business and political life toward the end of the 19th century.

Arriving in Honolulu from Boston in 1858, JB Atherton worked first for the firm of DC Waterman, before taking a position with the larger company of Castle and Cooke.

In 1865, JB Atherton married Juliette Montague Cooke, a daughter of the Reverend Amos Starr Cooke, one of the islands’ early missionaries. Together they had six children (including Frank.)

JB Atherton became a junior partner of Castle and Cooke; by 1894, as the sole survivor of the firm’s early leadership, he became president.

He worked closely with the Pāʻia Plantation and the Haiku Sugar Company on Maui, and in 1890 was one of the incorporators of the ʻEwa Plantation Company. Together with BF Dillingham, he organized the Waialua Agricultural Company, Ltd and became the first president

Atherton served for many years the president of Castle and Cooke, one of the “Big Five” companies in Hawaiʻi. At Castle and Cooke, he distinguished himself as an energetic and progressive leader, who helped transform Hawaii’s economy away from the single agricultural crop of sugar toward greater diversity.

Eventually, Frank C Atherton would become vice-president and then president of Castle and Cooke.

For 60 years the “Atherton House” was the home of the Atherton family; the Atherton's children donated it to the University of Hawaiʻi in 1964 to serve as a home for the University of Hawaiʻi president – the University named the home “College Hill.”

While it is the designated home for the University of Hawaiʻi president, and now bears the name "College Hill," it didn't get its name because the UH president lives there. (The Mānoa residence was built five years before the University was founded.)

Oʻahu College - as Punahou School used to be called - was located nearby. Thus, the Mānoa Valley section where Frank and Eleanore Atherton had their country home was called "College Hills Tract."

The image shows Atherton House – College Hill in its earlier years. In addition, I have included other related images in a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

© 2013 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Kaʻahumanu Wall

In the early 1800s, the city of Honolulu went as far as South Street; Kawaiahaʻo Church and Mission Houses (on King Street, on the Diamond Head side of town) were at the edge and outskirts of town.

The flat area between Mānoa and Honolulu was known as Kulaokahu‘a – the “plains.” It was the comparatively level ground below Makiki Valley (between the mauka fertile valleys and the makai wetlands.) This included areas such as Kaka‘ako, Kewalo, Makiki, Pawaʻa and Mōʻiliʻili.

Queen Kaʻahumanu was Kamehameha’s favorite wife. When he died on May 8, 1819, the crown was passed to his son, Liholiho, who would rule as Kamehameha II. Kaʻahumanu created the office of Kuhina Nui (similar to premier, prime minister or regent) and ruled as an equal with Liholiho.

On December 4, 1825, Queen Kaahumanu was baptized into the Protestant faith and received her new name, Elizabeth, then labored earnestly to lead her people to Christ.

In 1829, at the suggestion of Queen Kaʻahumanu, Governor Boki and Liliha gave the lands of Ka Punahou to Hiram and Sybil Bingham, leaders of the first missionary group to Hawaiʻi. Bingham then gave the land to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) to establish Punahou School.

The Binghams built their home there; Kaʻahumanu wanted to be close to them and built hers nearby (the Binghams later built an adobe house, with thatched roof.) A memorial boulder near Old School Hall and the Library marks the location of the makai door of the Bingham home.

Just as in other outlying areas around the islands, roaming cattle became a nuisance. Recall that in the early-1790s Captain George Vancouver gave Kamehameha I gifts of several cattle (a new species to the islands) and Vancouver strongly encouraged Kamehameha to place a 10‐year kapu on them to allow the herd to grow.

In the decades that followed, cattle flourished and turned into a dangerous nuisance. Vast herds destroyed natives’ crops, ate the thatching on houses, and hurt, attacked and sometimes killed people. (Kamehameha III later lifted the kapu in 1830.)

To protect the Bingham’s property and surrounding areas, in 1830, Queen Ka‘ahumanu ordered that a wall should be built from Punchbowl to Mōʻiliʻili. “The object of the structure was to keep cattle grazing on the plains from intruding upon the cultivated region towards the mountains.” (Hawaiian Gazette October 29, 1901)

“Kaahumanu's wall came from “the reef” (suggesting it was made of coral.) It is an Interesting fact many of the prisoners who built it were serving time for religion's sake. After the native's had cast down their idols and been converted, they turned against all forms of idolatry with the zeal new proselytes.” (Hawaiian Gazette October 29, 1901)

“When the Roman Catholic worship came in, the chiefs mistook the use of images' for idolatry and threw a great many Catholics into prison. The labor which went into the Kaahumanu wall included theirs.” (Hawaiian Gazette October 29, 1901)

“Years afterwards when Curtis Lyons went into the Survey office and laid the streets on the plains he named the thoroughfare which ran alongside the great wall, Stonewall street.” (Hawaiian Gazette October 29, 1901)

The wall followed a trail which was later expanded and was first called Stonewall Street. It was also known as “Mānoa Valley Road;” later, the route was renamed for the shipping magnate, Samuel G. Wilder (and continues to be known as Wilder Avenue.)

While the street was initially called “Stonewall Street,” it does not necessarily immediately suggest the wall was made of rocks.

A decade later the Kawaiahaʻo Church was constructed, it was commonly called the “Stone Church.” However, it is made of giant slabs of coral hewn from ocean reefs, as were other structures, at the time.

Likewise, “(s)uch blocks still appear in the Kawaiahao structure. In the ancient parsonage back of it and in the old house of government next door to the Postoffice and the material for the fence which fronted the “Hale” on Merchant street.” (Hawaiian Gazette October 29, 1901)

However, a later reference suggests the wall, at least at Punahou, may have been made of “stone.” The Friend, in a summary on Punahou history stated, “To protect the Manoa land from grazing cattle she (Kaʻahumanu) called on the governor, Kuakini, to build a long stone wall at its makai side. To mark the boundary, at the makai entrance, two large stones were set up.” (Damon, The Friend, March 1924)

The ‘Pōhaku’ book (Cheevers) suggests this same rock wall configuration, rather than the coral construction noted in the 1901 Hawaiian Gazette article. Pōhaku notes, "About 2,000 men worked on it as each chief was responsible for building one fathom (six feet) of its almost two-mile length (or approximately six-feet of dry laid rock wall, five feet high, per man)."

Irrespective of The Friend’s reference to the “reef,” the rock material in the Kaʻahumanu stone wall appears the most plausible. The disappearance of the Queen Kaʻahumanu wall is due to the street widening order of the Board of Public Works.

This wasn't the Islands' only significant cattle wall. Between 1830 and 1840, Governor Kuakini built a 6-mile wall (from Kailua to Keauhou, on Hawaiʻi Island) that separated the coastal lands from the inland pasture lands (Ka Pā Nui o Kuakini - the Great Wall of Kuakini.)

Punahou’s dry stack rock wall along Punahou Street was constructed in 1834. The night-blooming cereus (known in Hawaiʻi as panini o kapunahou) that today continues to cover the Punahou walls (that back in 1924 was noted to have “world-wide reputation and interest”) was planted in 1836 by Sybil Bingham (Hiram’s wife) from a few branches of the vine she received from a traveler from Mexico. (The Friend)

The image shows Punahou Street and Sybil Bingham’s night-blooming cereus in 1900 ((HSA) - this is not part of the Kaʻahumanu wall.) In addition, I have added other related images in a folder of like name in the Photos section on my Facebook and Google+ pages.

Follow Peter T Young on Facebook

Follow Peter T Young on Google+

© 2013 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Sunday, October 14, 2012

Mānoa

Mānoa translates as "wide or vast" and is descriptive of the wide valley that makes up the inland portion of this ahupuaʻa.

The ahupuaʻa of Mānoa has been a well-populated place. The existence of heiau and trails leading to/from Honolulu indicate it was an important and frequently traversed land.

John Papa ʻI'i wrote of the many trails leading into and throughout Honolulu and the surrounding areas. A trail led out of town at the south side of the coconut grove of Honuakaha and went on to Kalia. From Kalia it ran eastward along the borders of the fish ponds and met the trail from lower Waikīkī. The trail went above the stream to Puʻu o Mānoa.

The evidence of numerous agricultural terraces indicates an abundant food source, probably to support a fairly large population. Its inclusion in many legends and tales also suggests Mānoa Ahupua'a was a significant and well-loved area.

One legend explains Mānoa misty rain, the weeping in grief by a mother, Kuahine, for the death of her beautiful daughter Kahalaopuna (“Ka Ua Kuahine O Mānoa” (the Kuahine rain of Mānoa.))

Mānoa Valley was a favored spot of the Ali‘i, including Kamehameha I, Chief Boki (Governor of O‘ahu), Ka‘ahumanu, Ha‘alilio (an advisor to King Kamehameha III), Princess Victoria, Kana‘ina (father of King Lunalilo), Lunalilo, Ke‘elikōlani (half sister of Kamehameha IV) and Queen Lili‘uokalani.

Mānoa was given to the Maui chief Kame‘eiamoku by Kamehameha I after his conquest of O‘ahu. After Kame‘eiamoku death, the land was inherited by his son Ulumāheihie (or Hoapili), who became the governor of Maui during the reigns of Kamehameha II and Kamehameha III.

Liliha, the daughter of Hoapili, inherited the lands in 1811 and brought them with her to her marriage with the high chief Boki, governor of O‘ahu.

In early times Mānoa Valley was socially divided into “Mānoa-Aliʻi” or “royal Mānoa” on the west, and “Mānoa-Kanaka” or “commoners’ (makaʻāinana) Mānoa” on the east.

An imaginary line was said to have been drawn from Puʻu O Mānoa (Rocky Hill) to Pali Luahine. The Ali‘i lived on the high, cooler western (left) slopes; the commoners lived on the warmer eastern (right) slopes and on the valley floor where they farmed.

Mānoa is watered by five streams that merge into the lower Mānoa Stream: ‘Aihualama (lit. eat the fruit of the lama tree), Waihī (lit. trickling water), Nāniu‘apo (lit. the grasped coconuts), Lua‘alaea (lit. pit [of] red earth) and Waiakeakua (lit. water provided by a god). (Cultural Surveys)

In 1792, Captain George Vancouver described Mānoa Valley on a hike from Waikīkī in search of drinking water: “We found the land in a high state of cultivation, mostly under immediate crops of taro; and abounding with a variety of wild fowl chiefly of the duck kind … The sides of the hills, which were in some distance, seemed rocky and barren; the intermediate vallies, which were all inhabited, produced some large trees and made a pleasing appearance. The plains, however, if we may judge from the labour bestowed on their cultivation, seem to afford the principal proportion of the different vegetable productions …” (Edinburgh Gazetteer)

One century later, before it was urbanized, Mānoa Valley was described by Thrum (1892:) “Manoa is both broad and low, with towering hills on both sides that join the forest clad mountain range at the head, whose summits are often hid in cloud land, gathering moisture there from to feed the springs in the various recesses that in turn supply the streams winding through the valley, or watering the vast fields of growing taro, to which industry the valley is devoted. The higher portions and foot hills also give pasturage to the stock of more than one dairy enterprise.”

Handy (in his book Hawaiian Planter) writes that in ancient days, all of the level land in upper Mānoa was developed into taro flats and was well-watered, level land that was better adapted to terracing than neighboring Nuʻuanu. The entire floor of Mānoa Valley was a “checkerboard of taro patches.”

Oahu's first sugar plantation was established here in 1825, by an Englishman named John Wilkinson. Wilkinson died in 1826, the mill for the sugar was moved to Honolulu.

The plantation was sold and new owners wanted to turn it into a distillery. When Ka‘ahumanu heard of this, she was outraged and made Boki give them to Hiram Bingham and his wife as a base for mission work (and later, Punahou School.)

The well-watered, fertile and relatively level lands of Mānoa Valley supported extensive wet taro cultivation well into the twentieth century. Handy and Handy estimated that in 1931 “there were still about 100 terraces in which wet taro was planted, although these represented less than a tenth of the area that was once planted by Hawaiians.” (Cultural Surveys)

In the early part of the nineteenth century, the Japanese began to move in to the upper valley to start truck farms, growing strawberries, vegetables, such as Japanese dryland taro, Japanese burdock, radishes, sweet potatoes, lettuce, carrots, soy beans and flowers to sell to the Honolulu markets.

“Though the valley is under almost complete cultivation of taro, largely by Chinese companies, an effort was made by them in 1882 to divert it to the growth of rice, but after two years struggle with high winds, cold rains and myriads of rice birds it was abandoned.” (Thrum, 1892)

Today, Mānoa is primarily a residential community in Honolulu’s Primary Urban Center. It is home to over 20,000 permanent residents and University of Hawaiʻi-Manoa (with a student body population of around 20,000) (and several other schools, businesses, etc.)

The image shows Mānoa Valley taro loʻi (UH Heritage, 1890.) In addition, I have added other related images in a folder of like kind in the Photos section on my Facebook page.

http://www.facebook.com/peter.t.young.hawaii

© 2012 Hoʻokuleana LLC

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

-late+1910s.jpg)

.jpg)

-PPWD-17-3-027-1900.jpg)

-ca_1890.jpg)